Good Morning Team.

This is the last warning you’re going to get for a while on bonds - I’m about to start a new contract which is going to command a lot more of my time.

But I feel the moral need to warn you all, in plain English, about the risks in the global markets that are being - to my mind anyway - completely ignored.

Bitcoin rose to a record high of >$109,000 today. This isn’t really a record high (a large part of the rise is based in the reality that the US Dollar is weakening - in GBP terms, we’re not close).

But symbolically, it matters.

Gold’s back above $3,300 an ounce, and going from strength to strength.

This is great if you hold BTC or gold miners. But not so much for everyone else.

I cannot stress this enough - read this article. Understand it.

You don’t need to agree with it, but you do need to be informed.

Japanese Chaos

Japan’s long-term bond market is showing signs of real structural stress.

Yields on 30 year Japanese Government Bonds have surged to 3.14%, the highest level in history. The 40 year bond has jumped past 3.63%, with no bids — meaning no one was willing to buy either maturity for two consecutive days.

These are not routine market fluctuations. They are rare and severe disruptions that point to a breakdown in market functioning.

For decades, Japan has operated under a policy of Yield Curve Control, introduced by the Bank of Japan to suppress interest rates across the yield curve.

Under YCC, the BoJ targeted the 10 year yield at near-zero levels, intervening directly in the market to cap yields and keep borrowing costs ultra-low.

And this approach has worked for years in a deflationary environment. However, the BoJ only ever partially controlled the long end of the curve (30 and 40 year bonds), where investors are more sensitive to inflation expectations and duration risk.

Now that inflation pressures have risen globally, the long end is no longer responding to central bank signals, and is instead repricing sharply.

This is a big, big problem.

And it’s not a Japan-specific issue.

Japan’s bond market is the second-largest sovereign debt market in the world. Japanese institutions, especially banks, life insurers and pension funds, are major global investors.

Because of chronically low yields at home, they have historically bought large quantities of foreign debt, including US Treasuries and European government bonds, often using FX hedges to protect against currency risk.

When Japanese yields rise, those foreign investments become relatively less attractive, especially after accounting for the cost of hedging currency exposure.

This sets off a global chain reaction:

Japanese capital begins to return home, as institutions start selling US Treasuries and other foreign assets to reinvest in higher yielding domestic bonds.

This puts downward pressure on US Treasury prices (and upward pressure on yields) at a time when the US is rapidly increasing debt issuance, with somewhere in the regions of $7-9 trillion of US debt maturing or needing refinancing in 2025.

The cost of hedging foreign bond positions (especially in dollars) has spiked. FX-hedged returns on US Treasuries are now negative for Japanese investors, providing a further incentive to sell.

This worsens liquidity conditions globally. Stress is bleeding into other major financial centers as markets adjust to a world without a reliable Japanese bid.

The US bond market is already showing symptoms of this stress.

While the 2-year yield remains relatively stable around 4%, longer-term yields are surging: around 4.5% on the 10 year, and over 5% on the 30 year, the highest it’s been since November 2023.

Importantly, this steepening of the yield curve is not driven by optimism about growth but instead reflects a scarcity of long-term buyers and rising concerns about the sustainability of US sovereign debt.

Again, historically, Japan was a cornerstone buyer of US debt.

Their withdrawal leaves a hole that US domestic investors may struggle to fill. The Fed has already been quietly stepping in through stealth support operations, including swap lines, bond buyback programs and backdoor quantitative easing mechanisms, to keep auctions from failing.

The Fed is clearly preparing to act as the lender and buyer of last resort in case foreign demand collapses entirely.

This marks the unwinding of the global carry trade - where investors borrow in low-yielding currencies (like the yen) - to invest in higher-yielding assets abroad.

With Japanese yields now rising, the foundation of this trade is collapsing. To reiterate, the FX-hedged spread between US and Japanese bonds has evaporated, destroying the return profile.

What we are seeing is not just a cyclical shift. It signals a broader repricing of sovereign debt risk.

Japan’s long-term yields are breaking first. Europe is already showing signs of strain, as seen in widening German-French yield spreads, suggesting rising fragmentation risks. The US, with its massive fiscal deficits and waning foreign demand, is likely to be the final, but hardest-hit, part of this repricing chain.

Every tick higher in JGB yields is now a volatility accelerant. It sends ripples across global foreign exchange markets, credit spreads, and interest rate volatility.

Financial systems that were built around stable, low-yielding sovereign bonds are being forced to adapt to a world where that assumption no longer holds.

This is the quiet start of what may become a larger, global debt crisis. The BoJ’s weakening control undermines confidence in the ability of central banks, globally, to maintain order in the sovereign bond markets.

If Japan, which is renowned for strong financial discipline and domestic ownership of debt, can lose control, then so can others.

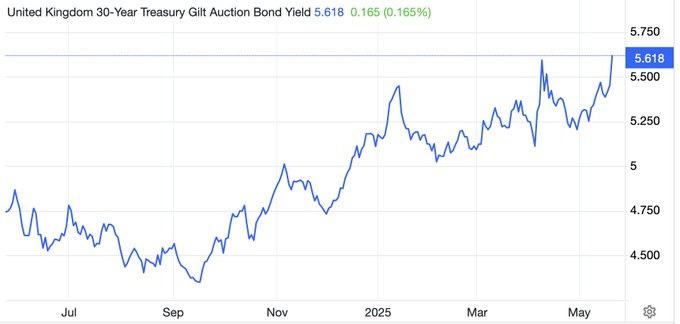

And in the UK, the long gilt yield is now at its highest this century.

The Stock Market Solution

To get the bond market under control, the powers that be will have to crash the stock market.

It’s the only answer. They’re not going to cut spending.

This isn’t academic. Rising bond yields don’t just affect governments. They ripple across the economy, increasing the cost of borrowing for businesses and consumers, making mortgages and credit more expensive, and putting downward pressure on the valuations of risk assets including equities.

Tech stocks and other long-duration investments, which depend on future cash flows, are particularly vulnerable.

As bond yields climb, investors demand more compensation for risk, which drags asset prices down. And the market is signaling that it no longer believes central banks can maintain control without a broader economic adjustment.

The fastest and most effective way to stabilise the bond market?

Break the stock market.

When equities sell off sharply, it triggers a chain reaction - consumer confidence drops, spending slows and inflation expectations fall.

That, in turn, drives capital out of risk assets and back into government bonds, stabilising yields. This is exactly what happened during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic panic. In both cases, crashing equities drove a flight to safety that brought yields down sharply.

In other words, central banks may be forced to tighten financial conditions until something breaks - and the stock market is the most likely pressure valve.

It’s not that policymakers want to cause a crash. But if inflation remains sticky, debt issuance remains high and bond buyers remain cautious, the only way to cool the system may be to crush investor risk appetite. That means engineering a major equity selloff to restore order.

And while the price will be high it may be the only remaining lever powerful enough to reset the system.

I think those at the top know this is going to happen.

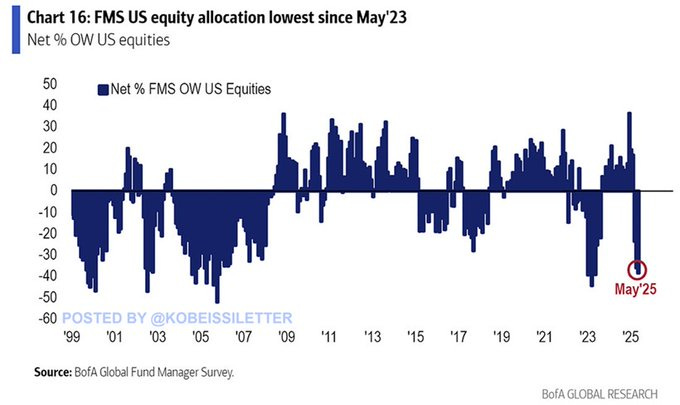

Institutional investors (hedge funds, pension managers and mutual funds) are growing increasingly cautious on US stocks.

According to Bank of America, as of early May, a net 38% of institutional investors were underweight US equities. This means that more institutions are cutting back their exposure than increasing it.

This marks the lowest level of institutional exposure since May 2023, and excluding that brief period, it's the lowest allocation since just before the 2008 financial crisis. The shift has been sharp - over the past five months, the net percentage of institutions underweight US equities has dropped by roughly 70 points, the steepest decline on record:

This isn't just a matter of reduced US exposure. It reflects a broader rotation in global equity preferences.

Institutional investors are increasingly favouring Eurostocks over US stocks. The difference between investors overweighting Eurozone equities versus US equities has hit a net spread of around 75%, the widest since October 2017. Just four months ago, that same metric was at -62%, meaning the US was favoured.

That’s a 137-point swing in sentiment in less than half a year.

At the same time, retail investors are behaving very differently.

According to JP Morgan, retail bought the recent market dip with record enthusiasm. In a single three-hour window, retail traders poured $4.1 billion into US equities, the largest inflow ever recorded.

This divergence has set the stage for a classic standoff: institutions are defensively positioned while retail investors are chasing the rally.

This positioning gap means one side will eventually be proven right. Either institutions will be forced to chase the market and rotate back into equities, pushing prices even higher, or retail investors will have bought into a short-lived rally that doesn't hold.

My guess? The professionals will win.

Yes, I know Buffett is ‘retired.’

But he’s built a cash hoard so large it could buy every share of 476 companies in the S&P 500 at today’s prices. I know right?

Historically, he’s taken the long view and often been on the right side of market turns.

That’s it from me on the macro for a while.

I am not saying the entire system is on the verge of collapse. This market has been detached from the fundamentals for some time.

Just that anyone with an iota of intelligence should be keeping an eye on it.

Mr Archer

Interesting to see that US government receipts in April increased by $482 bn compared to March.

Perhaps it's a one off or perhaps tariffs are having an effect.

That number annualised would be $6tn of additional receipts combined with lower expenditure via DOGE would massively change the calculus here. US bond yields are irrelevant if the US government needs no bonds.

Best wishes for your new contract.

OB

' over the past five months, the net percentage of institutions underweight US equities has dropped by roughly 70 points, the steepest decline on record'.

I think this should read .. OVERWEIGHT US Equities. Just a typo, but a significant one.

CIAN OHEIGEARTAIGH